記事|山縣勉「観察」

I had known Tsutomu Yamagata for almost a decade when he brought his new work to show me around a year or so ago. He had been an early enthusiastic visitor to Zen Foto. His was on an unconventional path to becoming a photographic artist, having started as a salaryman in a huge Tokyo corporation. Yet he had been passionate about photography throughout his wholeadult life. He would tell me of his trips as a student and young man to visit New York photography galleries and see the work of the American masters, Arbus being a particular favourite. He had made a courageous lifestyle choice while bringing up a young family to leave a safe career in order to concentrate on his photographic practise.

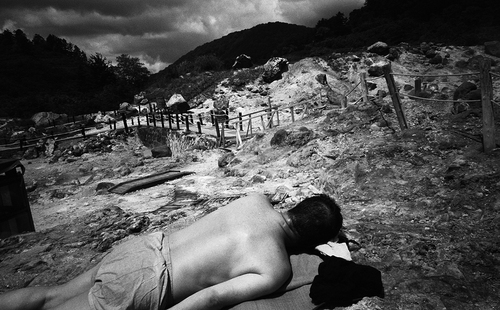

He had developed his darkroom skills over the years and spent painstaking hours with each subject to produce his first major series “Thirteen Orphans”, about the misfits gathering around Shinobazu-no-Ike in Tokyo’s Ueno district. This was one of our early Zen Foto publications in the soft cover B5 format. Some years later he came to show me his second series “Ten Disciples”. Where “Thirteen Orphans” was a carefully assembled series of portraits, in high quality medium format film, perfectly focused and uniformly posed, “Ten Disciples” was an impressionistic work incorporating Buddhist thinking. It was inspired by his discovery of a valley visited by terminal cancer sufferers, at a time he was looking for a place to help his own father who was suffering from that condition. Taken in grainy 35mm film it seems to be firmly in the “are, bure, boke” lineage of Japanese photography that emerged in the 1960s.

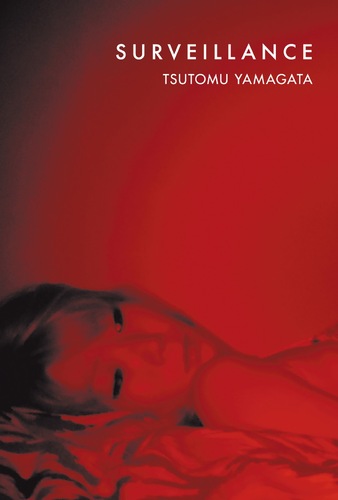

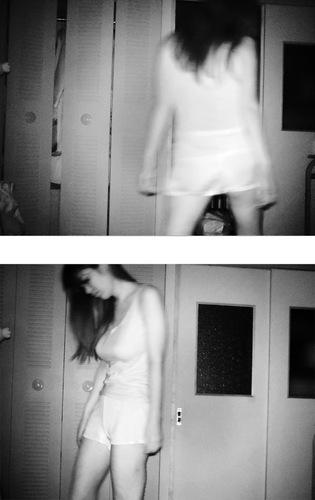

From Diane to Daido, Yamagata had explored two contrasting modes of expression, going from Diane (Arbus) to Daido (Moriyama). Perhaps, then, I should not have been as surprised as I was when he brought his third major series “Surveillance”, to show me. First of all, I would not have expected him to propose using low resolution digital images. In “Surveillance”, just published by Zen Foto, he has invited young women to place a trail camera in their apartments. While they are alone at home the trail camera shoots them automatically, releasing its silent shutter and invisible infra-red flash in their dark or dimly lit rooms. The women know that they are being photographed, but not when, and the photographer is not present until he takes the camera from the women at a later date and downloads the images back at his studio.

At first sight, there are some questions that naturally arise. This seems like a surreptitious form of photographing young women at unguarded moments at home, often in various stages of undress and undertaking all sorts of private activity. Is it akin to drilling a hole in a wall to take candid photographs in a womens’changing room or shower, or photographing up skirts from underneath a street grille? Such questions derive from the preconception of men seeking to gain a thrill from the sight of or even just the expectation and anticipation of innocent nakedness.

And yet, in “Surveillance” the women are all volunteers, no money has changed hands. The women place the camera where they choose and have agreed to publication of the results. Several also introduced Yamagata to their friends to be additional subjects of “Surveillance”.

By the way, one aspect of “Surveillance” that cannot be ignored lies in the title. We are all under surveillance, almost all of the time. Cameras observe us as we walk through the streets and in buildings. Our phones inform “big brother” of our location at all times. Our conversations are recorded and our images and videos. Our telephone microphones and cameras are “always on” at the discretion of the giant corporations which use our own data to manipulate our actions and form our wants. Given what Amazon, Google, Facebook and others are already doing, a trail camera in a woman’s apartment is a trivial additional intrusion to privacy. But I do not think that this is Yamagata’s main purpose in this work.

Yamagata has achieved an extreme detachment of the photographer’s influence on the scene, because he is not present in any real sense. The only way he could be less present would be to remove the camera altogether. In one sense, the removal of the photographer's presence makes the image as close to “reality” as possible.

According to Yamagata, on seeing the results, several women saw themselves anew and asked “is it really me?” The trail camera is low resolution and the resulting images smooth out the colours of the body, making them stylised (and beautiful) forms. The mechanism used for “are, bure, boke” aimed to prevent the literal representation of a scene. The blurred, out of focus, imperfectly exposed images somehow move us, probably because they thereby reveal something of reality that had been concealed or make us see things that would otherwise have been veiled. Yamagata has achieved something analogous; an image that has both removed us from reality while bringing us to a closer understanding of that reality.

Because the original images are low resolution, Yamagata chose to exhibit them in small size. This has the effect of making us look into them closely and we do appreciate better the beauty of the nude form, free of artifice, or at least free of awareness of any artifice. Yet I am also intrigued to see how these images would work at the other extreme, produced in very large size.

Yamagata’s career as an artist is still young, about as young as Zen Foto itself. We have grown up together. In these ten years, Yamagata has already produced three major series of works, each of which has been both an examination of the human condition and a significant addition to a genre of photography, from the formal social documentary of “Thirteen Orphans” to the impressionistic and frankly emotional beauty of “Ten Disciples” to the exploration of the human form in “Surveillance”.

Editor’s Note:

Photography Exhibition by Tsutomu Yamagata "SURVEILLANCE"

February 8 - March 2, 2019 at Zen Foto Gallery