Akira Tanno, photographer - Obituary / Ayako Koide

No matter how hard one attempts to use words to praise a photographer’s life of 89 years, a single phrase from the photographer himself is most convincing: ‘photography, out of the magic box.’ No matter how the history of photography was developed through modernity and technology, and its expression extended to fine art, Akira Tanno held onto his childhood memory of the magic within an elementary photographic device as the essence of his photography. His passion towards, and achievements in, photography originated in delight and wonder. Akira Tanno’s life of dedication to photography began when he encountered a camera at the Togo Camera store. As he recalled, it was as an elementary school kid wandering about a shopping district in his neighborhood. The black box appeared as a ‘magic box’ to him, and he carried this memory his entire life. His do-it-yourself spirit, already evident in his primary attempt to reproduce ‘the box’ with materials within his reach, along with the love and fascination for photography as miraculous phenomenon, led him to seek to be a photographer.

In the 1930s Japan was inclined towards militarism and this trend that dominated the entire society interrupted Tanno’s path to photography. Nevertheless, the end of war opened a path for Tanno who survived the war overseas and returned to Tokyo. He enrolled in the photography department of a university and finally met a well-informed professor to whom he would become an assistant. After several years working at the studio, he became a freelance photographer, one of the forerunners in this profession. His photography centred upon the shooting of musicians and performers, and as he recalled, ‘theatres and concert halls were my studio.’ His works capturing the leading musicians and ballerinas from abroad regularly appeared in music magazines. It was the 1950s and photographic technique was at a relatively elementary stage. There was a methodology in shooting an orchestra, calledObara-no-ippatsu (one shot by Obara) referring to the photographer who specialized in stage photography; taking only one shot with a flash at the very beginning of the show. Tanno, in contrast, did not use flash and shot from anywhere he wanted, and the images, blurred and grainy, captured vital moments of the performances. His stage photography, ranging from Western theatre to Japanese traditional performing arts, was published in photobooks entitledBallet: Bolshoi Theatre in Tokyo andMibu-Kyogen.

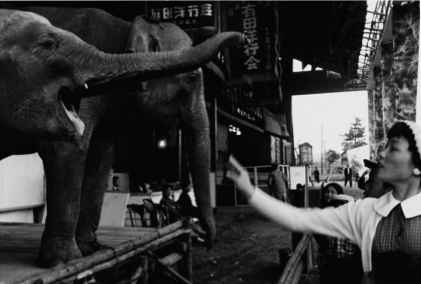

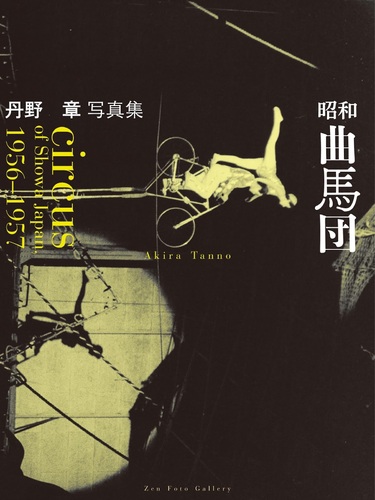

The subject of the ‘circus’ captured his attention in those days. Tanno was absorbed by the circus performances and stimulated by the childhood memory of peering the inside a circus tent, and produced a significant body of work in 1956-1957. His interest in the circus clearly distinguishes Tanno from the trend of other photographers of the time, notably the photography realism led by Ken Domon and Ihei Kimura. Whilst many other photographers looked for subjects or motifs that represented the shadows and debris of war, Tanno’s microscopic eyes were drawn to what I might call the left behind, or in-between, in the circus, whose development was interrupted by the war, in other words, the circus from the pre-war period.

The photography world, nevertheless, needed to ‘take flight’ from the deadlock that the photography realism reached, if we borrow the words of the photography critic Tatsuo Fukushima, who organized a series of three photography exhibitions ‘Eyes of Ten’ that started in 1957. Tanno was one of those emerging photographers who joined this show, along with Kikuji Kawada, Shun Kawahara, Ikko Narahara, Eikoh Hosoe, Masaya Nakamura, Akira Sato, Toyoko Tokiwa, Shomei Tomatsu, and Yasuhiro Ishimoto. Tanno’s ‘Circus’ was presented in the first of the ‘Eyes of Ten’ exhibitions.

The legendary photographers’ group VIVO emerged from the exhibitions. When Tanno learnt that the exhibition was not to be continued, he gathered five members from the exhibition, Akira Sato, Kikuji Kawada, Ikko Narahara, Eikoh Hosoe, and Shomei Tomatsu, with the idea of creating the ‘Magnum of Japan.’ Contrary to some perceptions of the group as an artist collective, VIVO did not undertake a collective project. They shared an office and darkroom and ran a photography agency together from 1959 to 1961. But each of them pursued their own vision and individual expression, so, according to Tanno, artistic interchange amongst members was only visible between each pair. Tanno moved this community of photographers with distinctive character and genius with his insight and leadership.

It was around this time that Japan was entering the ‘era of politics.’ Facing the 1960 Anpo, VIVO led the Japanese Photographers’ Association to take action protesting against the railroading of the revision of the U.S.-Japan military treaty. Although the members of VIVO were merely making a petition, this eventually drew much of the Japanese photography world of the time into the Anpo movement. It was also the time when Tanno’s interests inclined towards socio-political subjects, including Kawasaki industrial pollution, coalmines, Okinawa and U.S. military bases, as well as the snow country, all substantial subjects shared with other Japanese photographers. Tanno put an enormous effort into establishing copyright in photography, and initiated photographers’ groups to address socio-political issues such as anti-nuclear campaigns as well as the research group into the national constitution.

Akira Tanno passed away on 5th August, 2015, with much work left to be done, including, we hoped, the presentation of his previously unseen works, including those carrying messages that would resonate with the political climate of today’s Japan. There are myriad episodes that convey his outstanding achievement and contribution to Japanese photography, but as mentioned above, his photographic creation is inseparable to the notion of ‘photography as a magic box’. We see in his pictures an overflowing delight and wonder aligned with this principle—even in the most political images—as well as in the breadth of his practice, such as photographing, initiating movements and groups, writing and so on.

A photobook Circus of Showa Japan 1956-1957 was under preparation with Tanno when he was still alive, along with an exhibition of the same title. We would like to express the deepest regret to him and our inexpressible sorrow for not being able to hold this exhibition and publish the related book during his lifetime. After discussion with his executor we have agreed to honour the memory of Akira Tanno and to hold the exhibition as scheduled, from the 12th to the 19th of September 2015.

The ‘Circus’ series was shot in a short period of time towards the end of the 1950s. Within his long career it is of particular significance, representing the link between pre-war and post-war photography. So freely distinct from the major photographic movement of the time, the very personal and retrospective imagery helps us to see another aspect of post-war history. We sincerely hope that many of you will come to view the illuminating works of Akira Tanno.

Editors Note:

Akira Tanno was born in 1925 in Tokyo, Japan. In 1932 he moved to Nihon-Matsu and Aizu-Wakamatsu in Fukushima prefecture where his mother was originally from and spent one year there. In 1949 he graduated from the Department of Photography, College of Art, Nihon University. From 1947 he worked in advertising photography as assistant to Eigo Ohno from the University, and in 1951 became a freelance photographer. Since then his photographs of musicians on stage regularly appeared in the music magazineOngaku-no-Tomo (Friends of Music). He started to take photographs of ballet and circus performers during this period. In 1957 he exhibited the “Circus” series in the first edition of the “Eyes of Ten” exhibition (Konishiroku Photo Gallery, Tokyo) organized by the art critic Tatsuo Fukushima. In 1956 he established the photography agency VIVO along with Kikuji Kawada, Akira Sato, Shomei Tomatsu, Ikko Narahara and Eikoh Hosoe. The agency ran until 1961. In 1962 he participated in the “NON” exhibition organized by Tatsuo Fukushima. He started to take photographs with his interest in socio-political issues during this time, including Okinawa, the US military bases, coalmines, and metropolitan pollution. In 1972 he established a photography competition “Shiten” (Perspective) as a project of the Japan Realist Photographers Association where he had run the administration office since 1972. In 1978 he participated in the “VIVO: Contemporary Photography” exhibition (Santa Barbara Museum of Art, USA). Alongside these photography activities, since 1956 he has put an enormous effort into establishing copyright for photographic works in Japan, which had hitherto been in a primitive state. In 1960 he initiated a copyright campaign on behalf of the Japan Professional Photographers Society, which made a significant contribution to the revision of the photography copyright laws in 1970. In 1982 he started “Antinuclear Photographers’ Action” for the abolition of nuclear weapon along with Shomei Tomatsu and other photographers. In 2013 with Takeyoshi Tanuma he developed the “Photographers Group for Study of the Constitution of Japan” that has gained many advocates and continued its activity up to today. His solo-exhibitions include “Two Ballerinas” (Gekko Gallery, Tokyo, 1959), “Mino-Kyogen” (Canon Salon, Tokyo, 1975 and 1992), “The Post-War Japan Photographed by Akira Tanno” (Canon Gallery S, Tokyo, 2009), and “Heroes of the Underground” (Canon Gallery, Ginza, Sapporo, Fukuoka, 2013). His publications includeBallet: Bolshoi Theater in Tokyo (Ongaku no Tomo-Sha, 1958),Mibu-Kyogen (Koyo Shuppan-Sha, 1992),The World Ballet in Japan (Ongaku-no Tomo Sha, 1995), andRights to Photograph (Hon-no Izumi Sha, 2009).