Seiji Kurata — A Personal Reminiscence of His Later Years

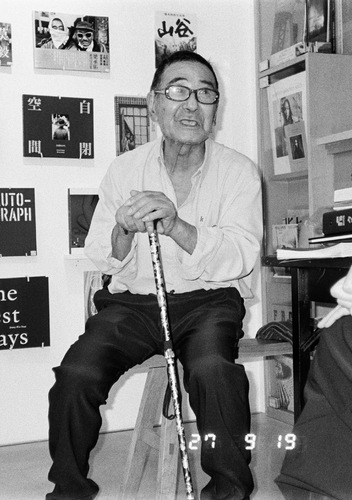

There are two things that occur to me in assessing our relationship with Seiji Kurata during the past decade. First, he was the most difficult person we have had to deal with. But the second is this: he was the one of whom we always said “he’s truly an artist”, and so we forgave him anything.

It was almost impossible to get hold of Kurata-san. He rarely answered the telephone. He did not use email. In the course of working on a project with him, the best we could do was to leave a message on his phone and wait. Invariably we would wait for weeks. A meeting would be arranged. Kurata-san liked to use his motorbike to get around the city. We worried about his safety. In the last few years I think he had given up riding his bike as he became more frail.

Kurata-san did not like to commit, and was always very nervous of making a decision. He felt that his work was too important to make decisions without long and careful consideration. If his work was not so phenomenal no-one could have endured his procrastination and prevarication. A meeting would finally be arranged, Kurata-san would arrive and embark upon a stream of consciousness, covering his work, his past and present troubles and resentments at the way he had been treated by the photographic establishment and many well-known photographers over many decades. He felt that life—and other people—had not treated him well. An hour or two later one of us would broach the subject of the day’s meeting. Kurata-san would hear the question and it would linger in his mind while he took off on a new tangent.

He knew his work was great, and wanted it more widely known, but he was also hyper sensitive to how it was released and shown. He had obviously had troubled relationships throughout his life. I think that we were the first and the only gallery at which he had anything resembling an enduring and continuing relationship.

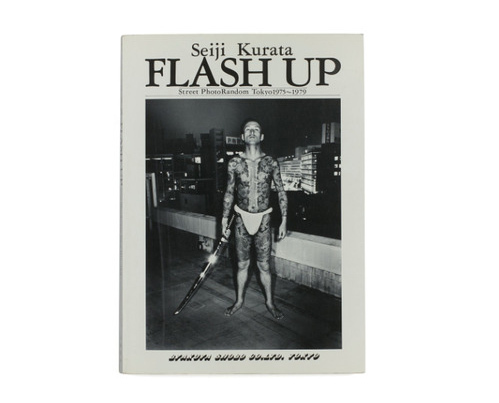

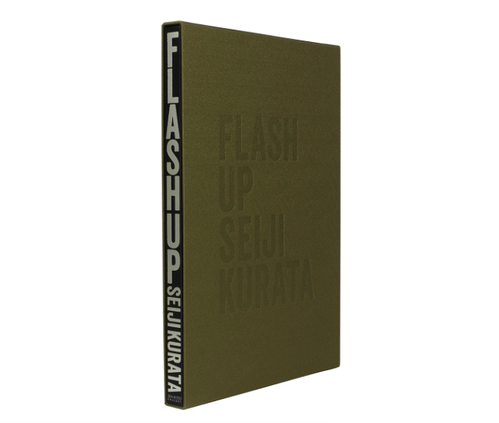

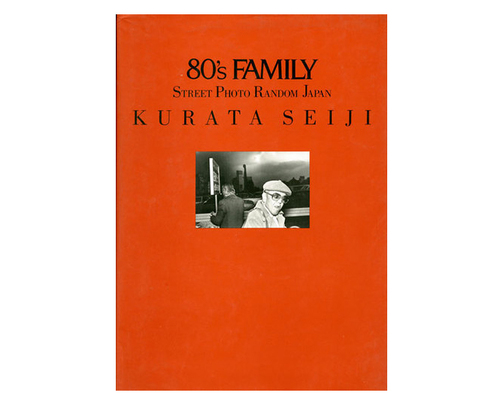

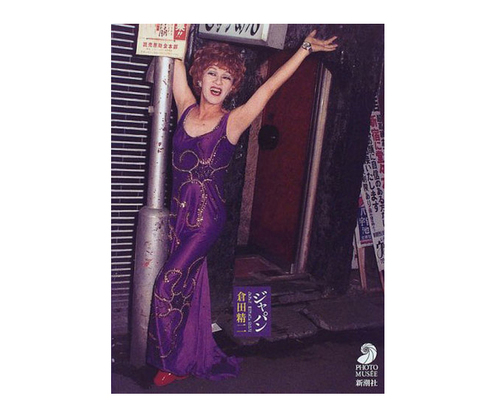

Kurata-san left us several wonderful books. Best known is his first book “Flash Up”. But the others are also distinctive and masterful.

Flash Up - Street Photo Random Tokyo 1975-1979 (1980, Byakuya Shobo)

Photo Cabaret (1983, Byakuya Shobo)

Dai-Asia (1990, IPC)

80’s Family - Street Photo Random Japan ‘80s (1991, JCCI)

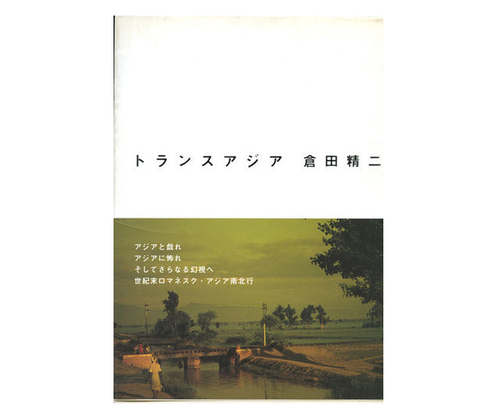

Trans-Asia (1995, Ota-Shuppan)

Japan (1998, Shinchosha)

Quest for Eros (1999, Shinchosha)

Trans Asia, Again! (2013, Place M)

Flash Up (New edition, 2013, Zen Foto Gallery)

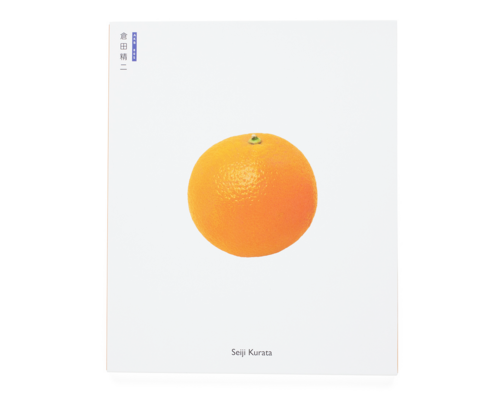

Toshi no Zokei (2015, Super Labo)

AKB 80’s (2016, Little Big Man Books / Zen Foto Gallery)

In addition, we will publish posthumously

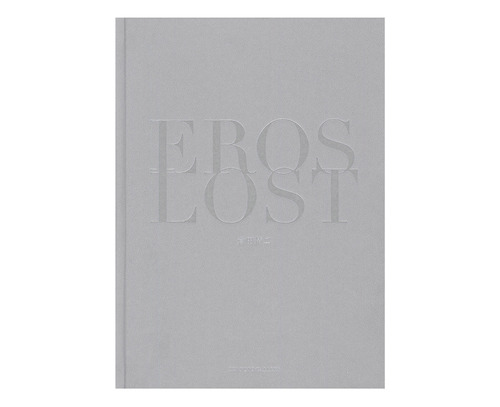

Eros Lost (2020, Zen Foto Gallery)

In addition to the books, Kurata-san did a lot of magazine work. This included photographing for the weekly scandal and news magazines, such as Friday and Focus and the astonishing Shashin Jidai, which regularly featured Kurata, Moriyama, Araki and their peers together with soft-core nudity. Kurata’s nudes were experimental and theatrical, quirky and humorous.

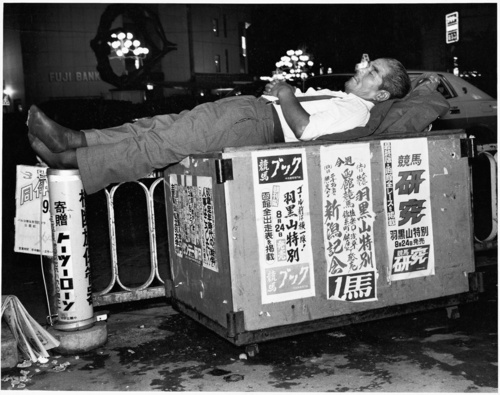

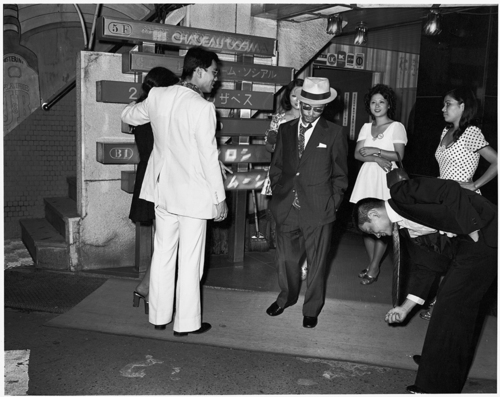

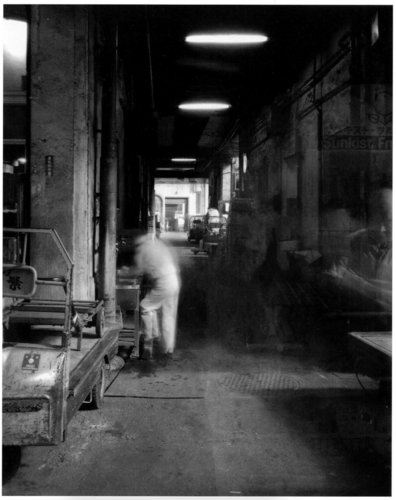

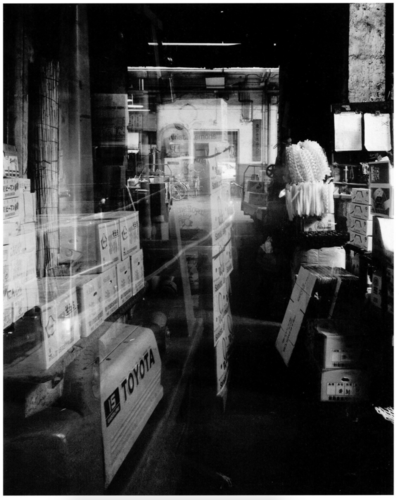

As with all artists, the works should speak for themselves. But my impression is that he could take a great photograph across most photographic genres, from streets to studio, from portraits to landscapes and in each would master the necessary techniques and open our eyes to new possibilities and to remarkable scenes. In Flash Up he was on the streets, finding action of all kinds. Hoodlums fighting, businessmen getting drunk in bars and being ripped off, mob chiefs holding court, traffic accident victims, transvestites getting ready for a night’s work and young would-be gangsters showing off their tattoos. He could also take cool photographs of the elevated expressways of Tokyo, cutting through the city like veins. AKB80’s is at first glance simple photography of a non-descript vegetable market - with loading bays, trucks, boxes and desultory labourers shifting the produce. Yet Kurata used extended and multiple exposures to show something beyond the mundane, to evoke the evolution of the marketplace and its significance in the history of Edo.

Kurata-san’s work had tremendous breadth in subject matter and technique. Carefully, he would work out how best to photograph each diverse subject, whether it should be in medium-format, large-format, black and white or colour, long exposure, with or without flash. In this he was truly a craftsman as well as an artist. He had graduated in Art from the Tokyo National University of Fine Art and Music, where he specialised in painting. And yet he ended up a photographic artist and worked as an engineer, with a workshop, to make a living outside of photography. But above all Kurata-san was an artist, always thoughtful and careful from conception through execution and presentation. We always used to acknowledge that, despite being the most difficult, Kurata-san was a maverick, but a maverick genius and the purest artist we worked with.

I knew Kurata-san only in the past decade during the time Zen Foto Gallery has been open, initially as an occasional visitor to the gallery and more regularly after we agreed to republish Flash Up. Flash Up is a landmark work. To leave behind a book like Flash Up would be enough for one lifetime, but I cannot help wondering what might have been. Kurata-san’s prickliness hampered the formation of the partnerships which are required to produce photography books. Our 2013 edition of Flash Up was his first publication in 14 years since Quest for Eros in 1999. I suspect that Kurata-san realised that he still had work to be done, and so 5 books have been published in the last 7 years, including Eros Lost.

As a Japanese man born in 1945 who worked in engineering and in the macho world of Japanese photography, Kurata-san as a rule did not reveal any tenderness or vulnerability. However, I once invited him to eat with me at home. After the meal I showed him to the train station. My young 4-year old son walked alongside Kurata-san and held his hand. A little later Kurata-san said that he had not held anyone’s hand in decades. I knew that it meant something to him. I hope that, near the end of his life, he was able to hold someone else’s hand.

Mark Pearson

May 2020

ー

Related Publication: