Issei Suda "Kamagasaki"

I first knew of Kamagasaki through Nagisa Oshima’s film ‘The Sun's Burial’. This film, released in 1960, had a huge impact on me, leaving a vivid image of the town in my mind.

‘Such brutal youthfulness, flourishing in the town of sex and violence!’ I am sure that the catchphrase appearing on the posters echoed the suppressed energy under the condition of post-ANPO-60, soon after the nationwide protests against the revision of the US-Japan Security Treaty in 1960. Set in the slum of day-labourers in midsummer, this film features places that are familiar to those who only know today’s Kamagasaki. I am still amazed with the director Oshima’s ability, making a whole piece out of the town, while being ‘scared when stepping into the area for the first time’ as written in his memoirs.

The characters in the film are not gloomy. They are eager to live with vigour and desire, but they are hopelessly bogged down, like small animals trapped in a bottomless swamp. Each of them has a certain inner strength, but not sufficient to break out from their situation. The film is a story made out of the cries of these people.

At the end of the film the female protagonist runs up to a man, asking: ‘Is society truly going to change? Are the tramps out there going to disappear?’ It has been fifty years since then. The times have changed, so too society, but as she presumed, the society that has long been awaited has not yet been achieved. Kamagasaki is still needed today.

In 2014, I was asked to take photographs of Kamagasaki and visited the town with little concern for how the town would affect me. My friend living in Osaka advised me to carry only small cameras to avoid drawing attention from the residents. I however ended up picking up two medium format cameras, which definitely attracted attention. Needless to say I have no interest in socio-political issues, never feeling any responsibilities to society. I was even once called an ‘observing’ photographer. I am merely a middle-aged stranger. I deserved those sharp glares and alarming jeers that I received from the residents throughout the shoot.

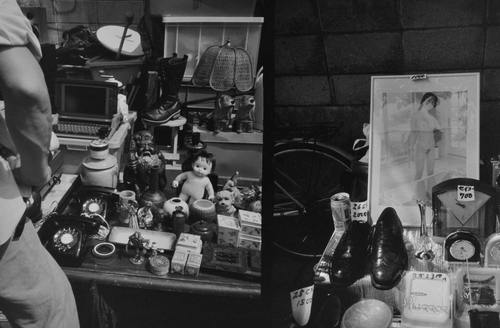

In fact I have visited Kamagasaki several times. Amidst the stench of the town and the glares of the men, what remains in my mind are the popular toy-doll Rika-chan displayed in a shelter built with irregular plywood shapes, and an erotic figure of a woman on a piece of girlie photography clutched in a man’s hand. I was even feeling as if I was in a Buddhist cathedral when I was eating with these men in the Airin Community Centre. Still, Kamagasaki was not a subject of my photography. I was just stopping by the area as a detour when I shot the nearby red light district of Tobita, or Shinsekai, the busiest downtown area of Osaka.

This was how I came to rediscover my negatives from 2000, which had remained untouched for fourteen years. It is also an unexpected pleasure to exhibit this series, which even I would not have looked at, if I had not had this invitation. Comparing these photographs taken in 2000 and 2014, I found that Kamagasaki has gradually been changing. Nevertheless, what has been changing the most is the destination of my own eyes. The town appeared differently as the state of my mind has changed.

While there are already many documentary works which are significant in their own right, what is collected in this photobook are mere fragments of the everyday lives of the town and the people living there. If someone discovers something new in this body of work, in these images that a passer-by saw in this town, it would be simply fortunate for me.

ーIssei Suda

Related Article

Issei Suda in Kamagasaki

(this link will direct you to a third-party site: shashasha.jp)

-

Kamagasaki, 2014 © Issei Suda

Kamagasaki, 2014 © Issei Suda -

Kamagasaki, 2014 © Issei Suda

Kamagasaki, 2014 © Issei Suda -

Kamagasaki, 2014 © Issei Suda

Kamagasaki, 2014 © Issei Suda -

Kamagasaki, 2014 © Issei Suda

Kamagasaki, 2014 © Issei Suda -

Kamagasaki, 2014 © Issei Suda

Kamagasaki, 2014 © Issei Suda -

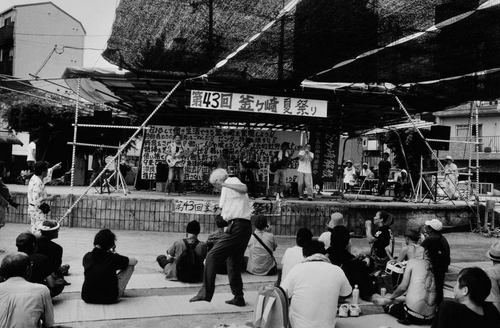

Kamagasaki, 2000 © Issei Suda

Kamagasaki, 2000 © Issei Suda -

Kamagasaki, 2000 © Issei Suda

Kamagasaki, 2000 © Issei Suda -

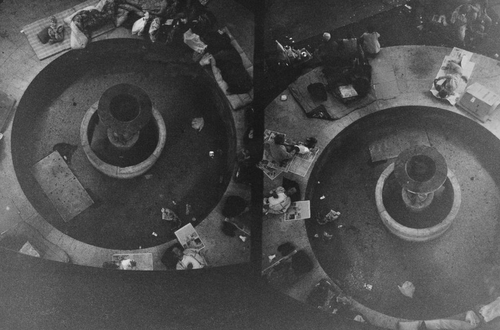

Kamagasaki, 2000 © Issei Suda

Kamagasaki, 2000 © Issei Suda -

Kamagasaki, 2000 © Issei Suda

Kamagasaki, 2000 © Issei Suda -

Kamagasaki, 2000 © Issei Suda

Kamagasaki, 2000 © Issei Suda