"Doyagai — Day Labouring Districts of Japan" Photographs by Seung-Woo Yang, Shoko Hashimoto, Haruto Hoshi, Issei Suda and Seiryu Inoue

The three doyagai are the districts where manual labourers gather in the three great Japanese cities of Tokyo, Yokohama and Osaka.

Japan’s cities have grown during the past century by absorbing migrants from the countryside. Sanya sits on the outskirts of the northern boundary of old Tokyo, a last stop for migrants from the great northern region of Tohoku before entering the city. In this marginal district the migrants find cheap doss-houses, and their establishments for drinking and whoring. Sanya sits to the north of the pleasure quarters of Shin-Yoshiwara. As the condemned man walked out of Tokyo, the last bridge to cross before reaching the execution ground was called Namida-bashi, or bridge of tears. Sanya is centred on Namida-bashi.

I cannot remember exactly how my fascination with Sanya began, but it was during Japan’s real estate bubble in the late 1980s. In 1987 I started working as an analyst covering Japan’s construction industry. Tokyo swept away the old to create a new pristine skyline that was built by labourers picked up daily from the streets of the old Sanya district.

I learned of Osaka's Kamagasaki through the photographs of Shunji Dodo in his book of photography, “Shinsekai: Mukashi mo ima mo” (新世界 むかしも今も). Published in 1986, this is a portrait of Shinsekai and its residents. Shinsekai is a pleasure district of Osaka and lies next to Kamagasaki on the border of southern Osaka, functioning for southern Osaka much as Sanya does for northern Tokyo.

The third Doyagai is Kotobukicho in Yokohama. I encountered it by chance as I wandered parts of southern Yokohama, and my daughter also helped out as a soup kitchen while she attended a nearby school.

I would take any opportunity to revisit these places and experience their unique atmosphere, even if it was sometimes an enervating experience.

I later came to several classics of Japanese photography that were created in the doyagai, notably the father of them all, “Kamagasaki” by Seiryu Inoue, who photographed the district in the 1950s and 1960s, during which period he also mentored the young Daido Moriyama.

These doyagai have been the subject of many photographers, and I list some of these books below. In the current exhibition, we are introducing works by four great contemporary photographers alongside a selection of works by Seiryu Inoue:

Kotobukicho : Seung-woo Yang “End of the Line ー Kotobukicho”

Kamagasaki : Haruto Hoshi “Nishinari, Osaka”

Kamagasaki : Issei Suda “Kamagasaki Magic Lantern”

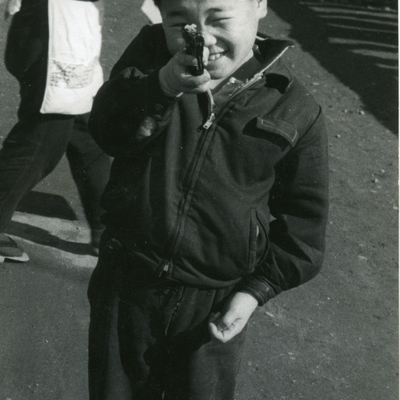

Sanya : Shoko Hashimoto “SAN'YA 1968.8.1 - 8.20”

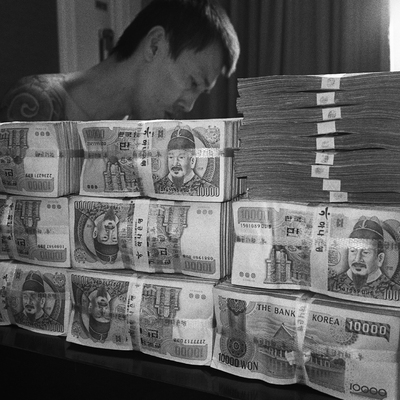

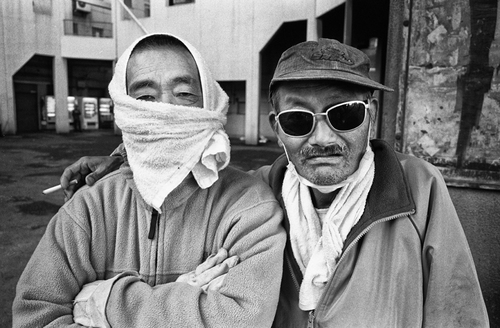

These works of Yang were taken over a decade ago. He spent time in Kotobukicho getting to know the place and the people before beginning to take photographs. The doyagai are areas where a camera is usually not welcome. Yang is a man who has turned his hand to many things, including manual labour, and this must have helped him blend into this very closed society and gain its trust.

Hoshi has taken remarkable photographs of the demi-monde of Shinjuku and we are pleased to introduce his arresting colour photographs taken in Kamagasaki.

During a period of teaching at the Osaka University of Arts Issei Suda would walk the streets of Kamagasaki with a Minox camera. More recently he visited during a midsummer festival to observe another aspect of the district. Suda was occasionally challenged for being there with a camera. Even today the locals are suspicious and nervous of outsiders, in part because illegal gambling and other activities take place on the streets.

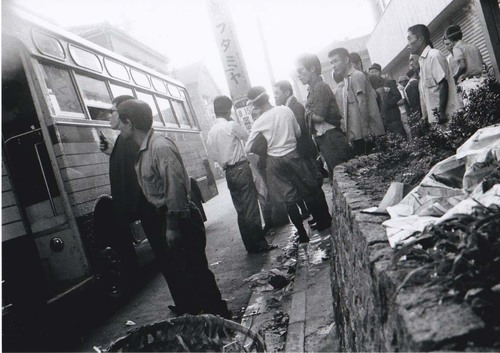

Hashimoto is best known for his photographs taken in his native Tohoku and other parts of rural Japan. But when he first came to live in Tokyo in the 1960s as a young man, he lived for some periods in Sanya and worked there as one of the casual day labourers. Later on, he went back to Sanya to take photographs.

The doyagai are special places. They reflect our essential selves, our origins. Stripped of masks. Stripped of possessions. Stripped of money. Stripped of power.

Most of us now live in cities. We think our lives are civilised. But how did we arrive here and come live our comfortable lives? In most cases our ancestors came from the fields in search of something better, and struggled through crushing difficulties. They passed through the Doyagai or their equivalent. I know almost nothing of my family history of more than 100 years ago, but even within the past short century, I know of family who have been itinerant coal miners, who have hanged themselves, who have lost a fiance in one war, who have died in another war, who have been separated from their family in wartime, who have been alcoholic and bankrupts, who have been destitute single mothers with small children. These are hardships that every family endures. The Doyagai bring us back to the realisation and to the common experience of our humanity.

ーMark Pearson (Zen Foto Gallery)

-

Seung-Woo Yang "End of the Line ー Kotobukicho” © Seung-Woo Yang

Seung-Woo Yang "End of the Line ー Kotobukicho” © Seung-Woo Yang -

Shoko Hashimoto "Sanya" © Shoko Hashimoto

Shoko Hashimoto "Sanya" © Shoko Hashimoto -

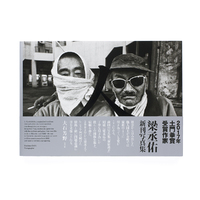

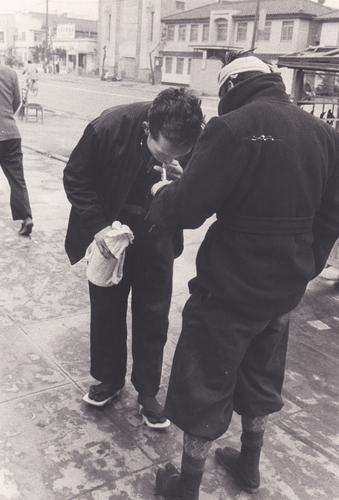

Seiryu Inoue "Kamagasaki", 1950-60's © Seiryu Inoue

Seiryu Inoue "Kamagasaki", 1950-60's © Seiryu Inoue -

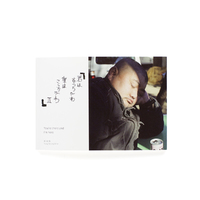

Issei Suda "Kamagasaki Magic Lantern", 2014 © Issei Suda

Issei Suda "Kamagasaki Magic Lantern", 2014 © Issei Suda -

Haruto Hoshi, Nishinari, Osaka, 2007-2014 © Haruto Hoshi

Haruto Hoshi, Nishinari, Osaka, 2007-2014 © Haruto Hoshi